Having watched a good deal of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, I get the sense that some viewers take away the message that just about every case of rape involves a stranger violently raping a woman, though this accounts for only a minority of rapes in the real world (Palmer, 1988). This may reflect the fact that women are themselves more fearful of being raped by a stranger than an acquaintance, as well as take more precautionary behaviors to guard against the former (Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1997). It is something of a mantra in our culture that rape is not about sex, but about violence - which is wrong, for the record (Palmer, 1988) - that probably also has a heavy contribution to the depictions of rape on shows like SVU. What makes these shows annoying - in addition to that heavily biased depiction of what rape is like - is that they normally also include some smug psychologist that apparently never progressed much beyond an introduction to psychology course - not unlike the writers, I'm sure - that gets called in to help out.

One person who may (metaphorically or actually) have watched too much Law & Order is

Amanda Marcotte. She's one of those "mad at evolutionary psychology without understanding what the hell she's talking about" kind of people, and it's my pleasure today to point out why she's wrong at some length.

Since Marcotte doesn't want to appear anti-science, she initially tries to co-opt the authority of two people only the "daringly stupid" would accuse of being anti-science:

P.Z. Myers and

Jerry Coyne. First, let me note that starting off with an explicit appeal to authority isn't the best course of action for any debate. That said, I certainly wouldn't accuse them of being anti-science, because that's a daringly stupid label. People are not opposed to science

in general; in fact, most people seem to love the idea of science. What people don't seem like is when scientists reach an unpalatable conclusion.

Beginning with the first point, Marcotte expresses skepticism about the results of a study that showed women generated a stronger grip strength in response to reading a rape scenario relative to a control story, but only when they were in the ovulatory phase of their cycle and not taking hormonal birth control (Petralia & Gallup, 2002):

"Which is how I'm going to approach contesting this article by Jesse Bering at Slate about the supposed evidence that women evolved to fight back against rape ... if they're ovulating...Some of them failed to present the evidence that Bering suggests they have--the handgrip study was one where some researchers found no variation over a menstrual cycle."

Let's be clear: the hypothesis is not that women

only evolved to fight back against rape

if they're ovulating; the claim is that women may have been selected to be

better able to fight back if they're ovulating, given the increased probability of conception and the resulting fitness costs. Fighting itself is generally not a costless act, and the conditions under which people are likely to fight should be expected to vary contingent on the potential costs and benefits. Women who do fight back are in fact more likely to stop a rape from being completed, but they also seem more likely to suffer physical injury (Ullman & Knight, 1993).

By "some researchers found no variation", it's not entirely clear what Marcotte is referring to (or rather, what Myers - whom she is parroting - is referring to), since she doesn't reference anything. I assume she's mentioning studies that found no variation across the menstrual cycle referenced by Petralia and Gallup that also

didn't involve any rape scenario story - the very thing that was hypothesized to be causing the effect. Comparing a study completely lacking an experimental manipulation to one with an experimental manipulation as evidence compromising the effect of the manipulation seems like a strange thing to do, probably because it's a stupid thing to do.

"Who's got time for actual replications? That sounds like work, and work isn't fun. This should be close enough"

Her next point is that one referenced in the very beginning: that rape is a violent crime, not a sexual one, even going so far as to say, "

Rape, in this case, is just a certain kind of wife-beating. It's best understood as throwing a punch with your penis." To quote Palmer quoting Hagen, "

If violence is what the rapist is after, he's not very good at it." When it comes to the use of force in rape, the vast majority of times it's used instrumentally - not excessively - if physical force is even involved at all. In this view, violence is the means to the end (sex), not the other way around. An example might clear this up a bit:

"The act of prostitution includes both a person giving money to another person and a sexual act. Does this mean that a man who goes to a female prostitute is motivated by a desire to give money to a woman?" (Thornhill & Palmer, 2000, p. 132)

I heard it's not technically illegal if your motivation was to give her money and the sex was just instrumental

Marcotte's final point would appear to be a stubborn misunderstanding of the difference between proximate and ultimate causation, as evidenced here:

"There's also the weird side assumption that features prominently in many half-baked evolutionary theories, which is that sex is strictly about reproduction in a species that has homosexuality, contraception, and old people who get it on...that rapists get off not on the chance to plant their seed (some, after all, use condoms!)..."

I'm pretty sure there's not a whole lot more to say about that, other than to point out it really does reinforce how little Marcotte knows about what she's attempting to criticize. At this point in the field's development, the only reason someone should make such a misguided mistake is near complete ignorance.

The only way this criticism could get any worse would be if Marcotte was foolish enough to imply evolutionary psychologists invoke genetic determinism and are attempting to give rapists a pass morally:

"...Bering's article downplays the severity of rape. It suggests that there's not much to be done about rape and that men are just programmed to do it... "

Nailed it!

One would think, given her initial concerns about not wanting to come off as anti-science, Marcotte would have included more

actual science in her post, but there really isn't any to be found. There's skepticism, ignorance, assertions, and moral outrage, but very little science. Perhaps it's worth quoting Palmer and Thornhill (2003), quoting Coyne on the matter, since Coyne is an authority to Marcotte:

"It is true that in recent decades, the discussion of rape has been dominated by such notions [as rape is not about sex, but about violence and power], though one must remember that they originated not as scientific propositions, but as political slogans deemed necessary to reverse popular misconceptions about rape"

Would you look at that; Coyne seems to think Marcotte is wrong about the "not sex" thing too.

References: Hickman, S.E. & Muehlenhard, C.L. (1997). College women's fears and precautionary behaviors relating to acquaintance rape and stranger rape.

Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 527-547

Palmer, C.T. (1988). Twelve reasons why rape is not sexually motivated: A skeptical examination.

The Journal of Sex Research, 25, 512-530

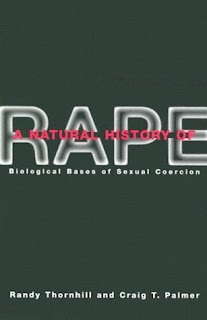

Palmer, C.T. & Thornhill, R. (2003) Straw men and fairy tales: Evaluating reactions to

A Natural History of Rape. The Journal of Sex Research, 40, 249-255

Petralia, S.M. & Gallup Jr., G.G. (2002). Effects of a sexual assault scenario on handgrip strength across the menstrual cycle.

Evolution and Human Behavior, 23, 3-10

Thornhill, R. & Palmer, C.T. (2000).

A natural history of rape: Biological bases of sexual coercion. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ullman, S.E. & Knight, R.A. (1993). The efficacy of women's resistance strategies in rape situations.

Psychology of Women Quarterly, 17, 23-38.