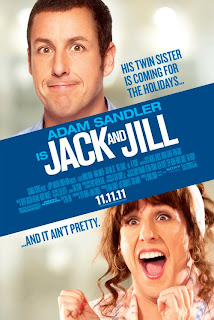

Jack and Jill (both played by Adam Sandler, for our purposes here) have been hanging out all night. While both have been drinking, Jill is substantially drunker than Jack. While Jill is in the bushes puking, she remembers that Jack had mentioned earlier he was out of cigarettes and wanted to get more. Once she emerges from the now-soiled side of the lawn she was on, Jill offers to drive Jack to the store so he can buy the cigarettes he wants. Along the way, they are pulled over for drunk driving. Jill wakes up the next day and doesn't even recall getting into the car, but she regrets doing it.

Was Jill responsible for making the decision to get behind the wheel?

More importantly, should the cop had let them off in the hopes that the drunk driving would have stopped this movie from ever being made?

Jack and Jill (again, both played by Adam Sandler, for our purposes here) have been hanging out all night. While both have been drinking, Jill is substantially drunker than Jack. While Jill is in the bushes puking, she remembers that Jack had mentioned earlier he thought she was attractive and wanted to have sex. Once she emerges from the now-soiled side of the lawn she was on, Jill offers to have sex with Jack, and they go inside and get into bed together. The next morning, Jill wakes up, not remembering getting into bed with Jack, but she regrets doing it.

Was Jill responsible for making the decision to have sex?

More importantly, was what happened sex, incest, or masturbation? Either way, if Adam Sandler was doing it, it's definitely gross.

According to my completely unscientific digging around discussions regarding the issue online, I can conclusively state that opinions are definitely mixed on the second question, though not so much on the first. In both cases, the underlying logic is the same: person X makes decision Y willingly while under the influence of alcohol, and later does not remember and regrets Y. As seen previously, slight changes in phrasing can make all the difference when it comes to people's moral judgments, even if the underlying proposition is, essentially, the same.

To explore these intuitions in one other context, let's turn down the dimmer, light some candles, pour some expensive wine (just not too much, to avoid impairing your judgment), and get a little more personal with them: You have been dating your partner - let's just say they're Adam Sandler, gendered to your preferences - who decided one night to go hang out with some friends. You keep in contact with your partner throughout the night, but as it gets later, the responses stop coming. The next day, you get a phone call; it's your partner. Their tone of voice is noticeably shaken. They tell you that after they had been drinking for a while, someone else at the bar had started buying them drinks. Their memory is very scattered, but they recall enough to let you know that they had cheated on you, and, that at the time, they had offered to have sex with the person they met at the bar. They go on to tell you they regret doing it.

Would you blame your partner for what they did, or would you see them as faultless? How would you feel about them going out drinking alone the next weekend?

If you assumed the Asian man was the Asian woman's husband, you're a racist asshole.

Our perceptions of the situation and the responsibilities of the involved parties are going to be colored by self-interested factors (Kearns & Fincham, 2005). If you engage in a behavior that can do you or your reputation harm - like infidelity - you're more likely to try and justify that behavior in ways that remove as much personal responsibility as possible (such as: "I was drunk" or "They were really hot"). On the other hand, if you've been wronged you're also more likely to try and lump as much blame on others as possible on the party that wronged you, discounting environmental factors. Both perpetrators and victims bias their views on the situation, they just tend to do so in opposite directions.

What you can bet on, despite my not having available data on the matter, is that people won't take kindly to having either their status as "innocent from (most) wrong-doing" or a "victim" be questioned. There is often too much at stake, in one form or another, to let consistency get in the way. After all, being a justified victim can easily put one into a strong social position, just as being known as one who slanders others in an unjustified fashion can drop you down the social ladder like a stone.

There's only one way to solve these problems once and for all.

References: Kearns, J.N. & Fincham, F.D. (2005). Victim and perpetrator accounts of interpersonal transgressions: Self-serving or relationship-serving biases? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 321-333

No comments:

Post a Comment